Python Practice

Table of contents

Vitual Environments

Python brew mac

conda & Anaconda distribution

Pycharm use virtualenv

PythonVScode

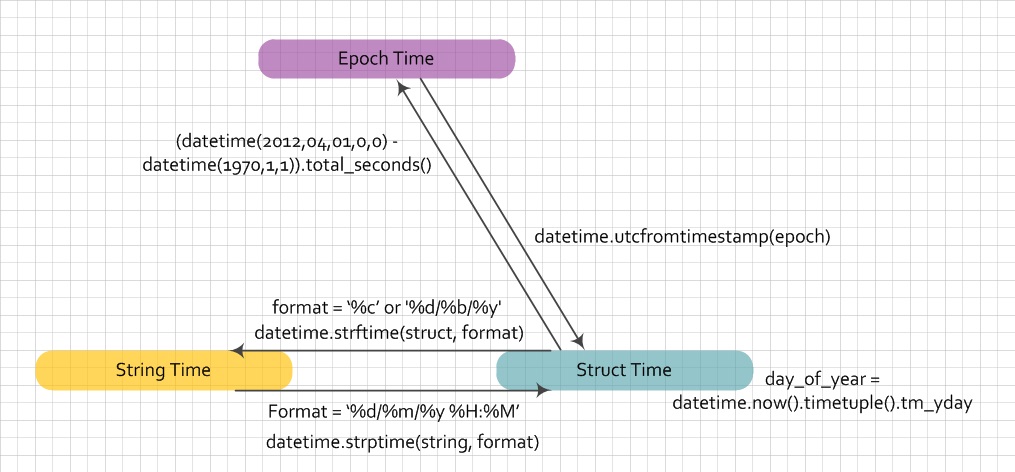

Date time

Division

Function arguments

Python installer

function __init__

Python objects and values

Python string encoding and manipulation

function lambda filter map reduce

Logs

Proxy

import error and dynamic import

Regular expression

Execute cmd command with subprocess

HTTP requests

Ignore exception and run next

List comprehension

Python load data

Python sort list of tuple

Vitual Environments

page link A Virtual Environment is a tool to keep the dependencies required by different projects in separate places, by creating virtual Python environments for them. It solves the “Project X depends on version 1.x but, Project Y needs 4.x” dilemma, and keeps your global site-packages directory clean and manageable.

For example, you can work on a project which requires Django 1.10 while also maintaining a project which requires Django 1.8.

virtualenv is a tool to create isolated Python environments. virtualenv creates a folder which contains all the necessary executables to use the packages that a Python project would need.

Install virtualenv via pip:

$ pip install virtualenv

Basic Usage

Create a virtual environment for a project:

$ cd my_project_folder

$ virtualenv venv

virtualenv venv will create a folder in the current directory which will contain the Python executable files, and a copy of the pip library which you can use to install other packages. The name of the virtual environment (in this case, it was venv) can be anything; omitting the name will place the files in the current directory instead.

This creates a copy of Python in whichever directory you ran the command in, placing it in a folder named venv.

You can also use the Python interpreter of your choice (like python2.7).

$ virtualenv -p /usr/bin/python2.7 venv

or change the interpreter globally with an env variable in ~/.bashrc:

$ export VIRTUALENVWRAPPER_PYTHON=/usr/bin/python2.7

To begin using the virtual environment, it needs to be activated:

$ source venv/bin/activate

The name of the current virtual environment will now appear on the left of the prompt (e.g. (venv)Your-Computer:your_project UserName$) to let you know that it’s active. From now on, any package that you install using pip will be placed in the venv folder, isolated from the global Python installation.

Install packages as usual, for example:

$ pip install requests

If you are done working in the virtual environment for the moment, you can deactivate it:

$ deactivate

This puts you back to the system’s default Python interpreter with all its installed libraries.

To delete a virtual environment, just delete its folder. (In this case, it would be rm -rf venv.)

After a while, though, you might end up with a lot of virtual environments littered across your system, and its possible you’ll forget their names or where they were placed.

Python brew mac

page link Generally, homebrew will install a formula into /usr/local/Cellar/formula and then place a link at /usr/local/bin/formula.

To make use of your installed formulae, make sure /usr/local/bin is in your $PATH. Show your $PATH by typing

echo $PATH

If /usr/local/bin is not in your $PATH, put this line at the end of your ~/.profile file.

export PATH=”/usr/local/bin:$Path”

Now, check what pythons are found on your OSX by typing:

which -a python

There should be one python found at /usr/bin/ (the Apple python) and one at /usr/local/bin/ which is the Homebrew python.

which python

will show you, which python is found first in your $PATH and will be executed when you invoke python.

If you want to know, where the executable is, show it by typing

ls -l $(which python)

This could look like this: lrwxr-xr-x 1 root wheel 68 7 Mai 13:22 python -> /usr/local/bin/python

This will work for pip as well.

If you show the results of this steps, we can probably help you much easier.

– UPDATE –

You have /usr/local/bin/python linked to /usr/local/Cellar/python/2.7.9/bin/python. -> brew install python worked.

show, if pip is installed by typing

| brew list python | grep pip |

You should see

/usr/local/Cellar/python/2.7.9/bin/pip

If not, check, if there are links, which are not done with brew install. Told you something like this:

“Error: The brew link step did not complete successfully

The formula built, but is not symlinked into /usr/local”

To force the link and overwrite all conflicting files:

brew link –overwrite python

To list all files that would be deleted:

brew link –overwrite –dry-run python

** NO standard Apple /usr/bin/python **

link from /usr/local/Cellar/python/2.7.9/bin/python to /usr/bin/python

ln -s /usr/local/Cellar/python/2.7.9/bin/python /usr/bin/python

This is necessary for all python scripts beginning with #!/usr/bin/python. Especialy easy_install will fail, if link is not there.

Other Notes

Running virtualenv with the option –no-site-packages will not include the packages that are installed globally. This can be useful for keeping the package list clean in case it needs to be accessed later. [This is the default behavior for virtualenv 1.7 and later.]

In order to keep your environment consistent, it’s a good idea to “freeze” the current state of the environment packages. To do this, run

$ pip freeze > requirements.txt

This will create a requirements.txt file, which contains a simple list of all the packages in the current environment, and their respective versions. You can see the list of installed packages without the requirements format using “pip list”. Later it will be easier for a different developer (or you, if you need to re-create the environment) to install the same packages using the same versions:

$ pip install -r requirements.txt

This can help ensure consistency across installations, across deployments, and across developers.

Lastly, remember to exclude the virtual environment folder from source control by adding it to the ignore list.

conda & Anaconda distribution

Honestly, above installation is complicated and fails easily. At the beginning I didn’t choose conda is because homebrew - conda together gives warnings, although I didn’t notice anything wrong. To overcome possible conflicts, just temporarily disable the conda path in your file ~/.bash-profile when brew doesn’t work.

After I read this article Conda: Myths and Misconceptions I’m certain that I should use Anaconda distribution and Conda to manage env as well as all in/external libs.

check current using env and all available envs

conda info --envs

create an environment

This is also a way that you manage multi python versions installed on your PC

conda create --name bunnies python=3 astroid babel

conda create --name snowflakes biopython

clone an env

conda create --name flowers --clone snowflakes

remove an env

conda remove --name flowers --all

change env de/activate

Linux, OS X: source activate snowflakes

Linux, OS X: source deactivate

Windows: activate snowflakes

Windows: deactivate

export env file and create env based on yml

conda env export > environment.yml

conda env create -f environment.yml

PYTHON PACKAGES AND ENVIRONMENTS WITH CONDA

Pycharm use virtualenv

Configure PyCharm

Select File, click Settings.

In the left pane, enter Project Interpreter in the search box, then click Project Interpreter.

In the right pane, click the gear icon, click More….

In the Project Interpreters dialog box, click the plus sign +, click Add Local.

Enter ~/virtualenvs/

PythonVScode

Using a light weight text editor with extension of Python debug is very pleasant. DonJayamanne Python extension is very good, it has autocomplete function as well, but you need to config it correctly. Here’s a sample entry in the User Settings file that will enable Google App Engine autocomplete and intellisense: doc link

# go to file->settings and type below in user settings, never touch the Master settings!!!

"python.autoComplete.extraPaths": [

"C:/Program Files (x86)/Google/google_appengine",

"C:/Program Files (x86)/Google/google_appengine/lib" ]

# to locate your anaconda

where anaconda

conda info

# to locate your specific pandas inside python

import pandas

import numpy

pandas.__path__

numpy.__path__

# ~\\AppData\\Local\\Continuum\\Anaconda2\\lib\\site-packages\\numpy

it’s also recommand to install gremlins plugin to display non-breaking space   etc.. those invisible characters.

Date time

from datetime import datetime

import time

import pandas as pd

import calendar

https://www.techatbloomberg.com/blog/work-dates-time-python/

Run have an idea of computation time, time.time() is useful.

Conversion between epochtime, structure time and string I use below function to avoid issues of daylight saving, timezone.

epochtime can be in [s] or [ms], it means the total seconds or milliseconds from 1970/01/01 till now.

You can also calculate with excel 2018/04/18 - DATE(1970,1,1) * 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000 [ms], using epochtime website you can verify your conversion.

| formatter | description | |

|---|---|---|

| “%a” | Locale’s abbreviated weekday name. | |

| “%A” | Locale’s full weekday name. | |

| “%b” | Locale’s abbreviated month name. | |

| “%B” | Locale’s full month name. | |

| “%c” | Locale’s appropriate date and time representation. | |

| “%d” | Day of the month as a decimal number [01,31]. | |

| “%H” | Hour (24-hour clock) as a decimal number [00,23]. | |

| “%I” | Hour (12-hour clock) as a decimal number [01,12]. | |

| “%j” | Day of the year as a decimal number [001,366]. | |

| “%m” | Month as a decimal number [01,12]. | |

| “%M” | Minute as a decimal number [00,59]. | |

| “%p” | Locale’s equivalent of either AM or PM. | |

| “%S” | Second as a decimal number [00,61]. | |

| “%U” | Week number of the year (Sunday as the first day of the week) as a decimal number [00,53]. All days in a new year preceding the first Sunday are considered to be in week 0. | |

| “%w” | Weekday as a decimal number [0(Sunday),6]. | |

| “%W” | Week number of the year (Monday as the first day of the week) as a decimal number [00,53]. All days in a new year preceding the first Monday are considered to be in week 0. | |

| “%x” | Locale’s appropriate date representation. | |

| “%X” | Locale’s appropriate time representation. | |

| “%y” | Year without century as a decimal number [00,99]. | |

| “%Y” | Year with century as a decimal number. | |

| “%Z” | Time zone name (no characters if no time zone exists). | |

| ”%%” | A literal ’%’ character. |

HTML example http://www.w3schools.com/html/html_tables.asp

Generate a list of timestamp

rng = pd.date_range('2016-08-01', periods= 10, freq='12H')

rng.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

array(['2016-08-01', '2016-08-01', '2016-08-02', '2016-08-02',

'2016-08-03', '2016-08-03', '2016-08-04', '2016-08-04',

'2016-08-05', '2016-08-05'],

dtype='|S10')

Check leap year:

calendar.isleap(datetime.now().timetuple().tm_year)

Division

By default, python2.7 division return only the rounded integer part. To force results into float try below

>>> from __future__ import division

>>> 2/3

>>> 0.6666666666666666

Function arguments

two common one

import argparser

import getopt

An example using only Unix style options:

>>> import getopt

>>> args = '-a -b -cfoo -d bar a1 a2'.split()

>>> args

['-a', '-b', '-cfoo', '-d', 'bar', 'a1', 'a2']

>>> optlist, args = getopt.getopt(args, 'abc:d:')

>>> optlist

[('-a', ''), ('-b', ''), ('-c', 'foo'), ('-d', 'bar')]

>>> args

['a1', 'a2']

Using long option names is equally easy:

>>> s = '--condition=foo --testing --output-file abc.def -x a1 a2'

>>> args = s.split()

>>> args

['--condition=foo', '--testing', '--output-file', 'abc.def', '-x', 'a1', 'a2']

>>> optlist, args = getopt.getopt(args, [

... 'condition=', 'output-file=', 'testing'])

>>> optlist

[('--condition', 'foo'), ('--testing', ''), ('--output-file', 'abc.def')]

>>> args

['a1', 'a2']

# "--help" and "-h" style combined:

>>> s = '--condition=foo --testing --output-file abc.def -x a1 a2'

>>> args = s.split()

>>> args

['--condition=foo', '--testing', '--output-file', 'abc.def', '-x', 'a1', 'a2']

>>> optlist, args = getopt.getopt(args, 'x', [

... 'condition=', 'output-file=', 'testing'])

>>> optlist

[('--condition', 'foo'), ('--testing', ''), ('--output-file', 'abc.def'), ('-x', '')]

>>> args

['a1', 'a2']

In a script, typical usage is something like this:

import getopt, sys

def main():

try:

opts, args = getopt.getopt(sys.argv[1:], "ho:v", ["help", "output="])

except getopt.GetoptError as err:

# print help information and exit:

print str(err) # will print something like "option -a not recognized"

usage()

sys.exit(2)

output = None

verbose = False

for o, a in opts:

if o == "-v":

verbose = True

elif o in ("-h", "--help"):

usage()

sys.exit()

elif o in ("-o", "--output"):

output = a

else:

assert False, "unhandled option"

# ...

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Note that an equivalent command line interface could be produced with less code and more informative help and error messages by using the argparse module:

import argparse

if __name__ == '__main__':

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('-o', '--output')

parser.add_argument('-v', dest='verbose', action='store_true')

args = parser.parse_args()

# ... do something with args.output ...

# ... do something with args.verbose ..

Combining Positional and Optional arguments Define firstly all positional arguments then start optional arguments. You can have help / extra information and display them. You can force argument type to int instead of default string. You can provide a default value for the argument.

import argparse

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description='A foo that bars',

epilog="And that's how you'd foo a bar")

parser.print_help()

parser.add_argument("square", type=int,

help="display a square of a given number")

parser.add_argument("-v", "--verbose", action="store_true",

help="increase output verbosity")

parser.add_argument('--example', nargs='?',

const=1, type=int)

args = parser.parse_args()

answer = args.square**2

if args.verbose:

print "the square of {} equals {}".format(args.square, answer)

else:

print answer

print args

print args.example

print args.info

nargs=’?’ means 0-or-1 arguments const=1 sets the default when there are 0 arguments type=int converts the argument to int

When run the python command with arguments use the double quotation “ instead of simple quotation’

Python installer

$ python setup.py sdist

This will create a dist sub-directory in your project, and will wrap-up all of your project’s source code files into a distribution file, a compressed archive file in the form of: TowelStuff-0.1.tar.gz

The compressed archive format defaults to .tar.gz files on POSIX systems, and .zip files on Windows systems.

Quick start.

To change package format, you can add --format=zip in your cmd command, available format.

Detailed tutorial to run with adding more files.

But now the dist should use new format wheel, .egg or .zip or .tar are all old way to package.

.whl file can be directly upload to PyPI and easily installed by any user, just run pip install <your package> Here is the link shows you how.

$ python setup.py bdist_wheel

function __init__

init.py can be added into any directory that you want python to search your defined modules.

Contents of the file can be either from modules import class or empty.

question link

Project

├───.git

├───venv

└───src

├───__init__.py

├───mymodules

│ ├───__init__.py

│ ├───module1.py

│ └───module2.py

└───scripts

├───__init__.py

└───script.py

script.py

import src.mymodules.module1

[...]

(venv)$ python src/scripts/script.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "src/scripts/script.py", line 1, in <module>

import src.mymodules.module1

ImportError: No module named src.mymodules.module1

anyfolder with __init.py inside can be considered as package in python. anymodule.py file can be considered as a module in python.

from myPackages import myModule

import myPackages.myModule

although init.py exists for each packages, but when run script.py directly, python doesn’t know the existance of mymodules nor src. We can move script.py under Project. Or we can specify in the script.py that […]/Project (where src located) is also sys.path.insert(0, [...]/Project). Alternativly You could add the /Project path as PYTHONPATH in the advanced system settings or .bash_profile, but it’s not a good practice especially you copy the current project and work with its copy, the copy could still import modules from original project and confuses you as module names are identical.

Python objects and values

link Think Python 2e

Object:

>>> a = 'banana'

>>> b = 'banana'

>>> a is b

True

Value:

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = [1, 2, 3]

>>> a is b

False

>>> a == b

True

>>> a = [1, 2, 3]

>>> b = a

>>> a is b

True

>>> b[0] = 42

>>> a

[42, 2, 3]

# b change values, a change as well

# avoid using in the above way!!!

>>> c = a[:]

>>> c[0] = 200

# a is not affected!!!

>>> a

[42, 2, 3]

Python string encoding and manipulation

when using json.dump or yaml.dump the text in file contains extra char such as !!Python/unicode or u, to eliminate them, using encoding option when dumping. possible solution

import yaml

yaml.dump(manifestSample, f, default_flow_style=False, allow_unicode=True, encoding='utf8')

To extract part of the dot seperated string s = 'www.google.com'</br>

Method 1 function find

>>> l = s.find('.')

>>> r = s.rfind('.')

>>> s[l+1 : r]

'google'

[Method 2 list comprehension]

>>> l = [i for i, chr in enumerate(s) if chr =='.']

[3, 10]

>>> s[l[0]+1 : l[1]]

'google'

[Method 3 function rsplit]

>>> s.rsplit('.')

['www', 'google', 'com']

>>> s.rsplit('.', 1)

['www.google', 'com']

function lambda filter reduce map

filter map reduce definitions by book pythontips combined usage with lambda function examples

general reading for lambda http://www.secnetix.de/olli/Python/lambda_functions.hawk</br> https://stackoverflow.com/questions/890128/why-are-python-lambdas-useful</br> https://pythonconquerstheuniverse.wordpress.com/2011/08/29/lambda_tutorial/</br>

>>> foo = [2, 18, 9, 22, 17, 24, 8, 12, 27]

>>>

>>> print filter(lambda x: x % 3 == 0, foo)

[18, 9, 24, 12, 27]

>>>

>>> print map(lambda x: x * 2 + 10, foo)

[14, 46, 28, 54, 44, 58, 26, 34, 64]

>>>

>>> print reduce(lambda x, y: x + y, foo)

139

>>> def make_incrementor (n): return lambda x: x + n

>>>

>>> f = make_incrementor(2)

>>> g = make_incrementor(6)

>>>

>>> print f(42), g(42)

44 48

>>>

>>> print make_incrementor(22)(33)

55

for people don’t like them, list comprehension is a good alternative

tricky part of filter(None, [None, 1,2,3,0, None, 4,5]) will ignore not only None, but also 0 in the list.

solution is to write your own list comprehension or Python3

MIT book to understand deeper about structure

Logs

Logging cookbook https://docs.python.org/2.7/howto/logging-cookbook.html

import logging

import auxiliary_module

# create logger with 'spam_application'

logger = logging.getLogger('spam_application')

logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

# create file handler which logs even debug messages

fh = logging.FileHandler('spam.log')

fh.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)

# create console handler with a higher log level

ch = logging.StreamHandler()

ch.setLevel(logging.ERROR)

# create formatter and add it to the handlers

formatter = logging.Formatter('%(asctime)s - %(name)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

fh.setFormatter(formatter)

ch.setFormatter(formatter)

# add the handlers to the logger

logger.addHandler(fh)

logger.addHandler(ch)

logger.info('creating an instance of auxiliary_module.Auxiliary')

a = auxiliary_module.Auxiliary()

logger.info('created an instance of auxiliary_module.Auxiliary')

logger.info('calling auxiliary_module.Auxiliary.do_something')

a.do_something()

logger.info('finished auxiliary_module.Auxiliary.do_something')

logger.info('calling auxiliary_module.some_function()')

auxiliary_module.some_function()

logger.info('done with auxiliary_module.some_function()')

A typical approach is to have something like the following at the top of a file:

import logging

log = logging.getLogger(__name__)

This makes log global, so it can be used within functions without passing log as an argument:

def add(x, y):

log.debug('Adding {} and {}'.format(x, y))

return x + y

Log with decorators https://www.freshbooks.com/developers/blog/logging-actions-with-python-decorators-part-i-decorating-logged-functions

Proxy

import os

os.environ['HTTP_PROXY'] = "http://xxx.com:80"

os.environ['HTTPS_PROXY'] = "http://xxx.com:80"

os.environ['http_proxy'] = "http://xxx.com:80"

os.environ['httpS_proxy'] = "http://xxx.com:80"

print os.environ['HTTP_PROXY']

print os.environ['HTTPS_PROXY']

## github and google will not use proxy settings

os.environ['NO_PROXY'] = 'github.com, google.com'

os.environ['no_proxy'] = 'github.com, google.com'

import error and dynamic import

It’s headache when you first run into the Python import error: No module named does exist. First make sure all your python paths do not contain whitespace. Then You can simply add your project into PYTHONPATH on Windows, for Mac you can play with $PYTHONPATH. But adding too many paths into PYTHONPATH is not good, you increase the chances to have the same function name in different paths. Suppose you clone this project locally and work on the copy, only original path is added. When you run test on the copy, no import error occurs, because python still import functions from the origin, and that is not what you expect. It’s hard to discover it untill you remember that a similar project with same module name exists in your PYTHONPATH.

PYTHONPATH is key to installing and importing third-party packages. When an import command is passed, python looks for the module/package in a list of places.

An alternative is to add search path temporarily only when project runs, and check the output of path, if Python finds your modules/packages

import sys

import os

sys.path.append(os.path.join(os.path.dirname(__file__), ".."))

print sys.path

When you receive a user uploaded module to use once your codes is finished, your codes needs to dynamically load the user module.

# Easy solution is to use Python magic function

module = __import__(module_name)

my_class = getattr(module, class_name)

instance = my_class()

# Another way is use module

import imp

Regular expression

multiline_str =

'name requested state instances memory disk urls

test-data-seed started 1/1 512M 1G test-data-seed.run.aws02-pr.ice.predix.io

test-rmd-datasource started 1/1 512M 1G test-rmd-datasource.run.aws02-pr.ice.predix.io

test-rmd-ref-app-ui started 1/1 64M 1G test-rmd-ref-app-ui.run.aws02-pr.ice.predix.io

test-websocket-server started 1/1 512M 1G test-websocket-server.run.aws02-pr.ice.predix.io

test-data-exchange started 2/2 512M 1G test-data-exchange.run.aws02-pr.ice.predix.io

test-data-exchange-simulator stopped 0/1 512M 1G test-data-exchange-simulator.run.aws02-pr.ice.predix.io'

find out all names with regular expression

import re

name = re.findall('^\S+', apps, re.M) # flag re.Multilines search line by line, \S+ anytimes non-white space characters, ^ line starting point

['name', 'perf-rabbitmq', 'perf-uaa', 'perf-acs', 'perf-asset', 'perf-time-series', 'perf-redis']

(?#...)

A comment; the contents of the parentheses are simply ignored.

(?=...)

Matches if … matches next, but doesn’t consume any of the string. This is called a lookahead assertion. For example, Isaac (?=Asimov) will match ‘Isaac ‘ only if it’s followed by ‘Asimov’.

(?!...)

Matches if … doesn’t match next. This is a negative lookahead assertion. For example, Isaac (?!Asimov) will match ‘Isaac ‘ only if it’s not followed by ‘Asimov’.

(?<=...)

Matches if the current position in the string is preceded by a match for … that ends at the current position. This is called a positive lookbehind assertion. (?<=abc)def will find a match in abcdef, since the lookbehind will back up 3 characters and check if the contained pattern matches. The contained pattern must only match strings of some fixed length, meaning that abc or a|b are allowed, but a* and a{3,4} are not. Group references are not supported even if they match strings of some fixed length. Note that patterns which start with positive lookbehind assertions will not match at the beginning of the string being searched; you will most likely want to use the search() function rather than the match() function:

>>> import re

>>> m = re.search('(?<=abc)def', 'abcdef')

>>> m.group(0)

'def'

This example looks for a word following a hyphen:

>>> m = re.search('(?<=-)\w+', 'spam-egg')

>>> m.group(0)

'egg'

(?<!...)

Matches if the current position in the string is not preceded by a match for …. This is called a negative lookbehind assertion. Similar to positive lookbehind assertions, the contained pattern must only match strings of some fixed length and shouldn’t contain group references. Patterns which start with negative lookbehind assertions may match at the beginning of the string being searched.

Tutorial of lookahead, lookbehind

(?=USD) place your start point at the beginning of |USD, the search pattern put before or after itself, behavior is different. (?<=USD) place your start point at the end of USD|, and then start to match, the search pattern put before or after itself, behavior is different check this https://regex101.com/ with example ‘100USD10’ with r’100(?=USD)’ get the number 100 before dollar; with r’(?<=USD)10’ get the number 10 after USD.

Execute cmd command with subprocess

To execute cmd command from Python environment, subprocess is the great helper. https://docs.python.org/2/library/subprocess.html

import subprocess

>>> call = subprocess.call(['ls'])

Lib Scripts unicows.dll

>>> call

0

>>> output = subprocess.check_output(['ls'])

>>> output

'Lib\nScripts\nunicows.dll\n'

>>> print output

Lib

Scripts

unicows.dll

subprocess.call() execute the command and print out the screen and return a status 0 when successful. subprocess.check_output() execute the command and save the screen output as a byte string, you have to print it out.

PS: args must be put inside the list []

if you like to live output message on screen, follow steps

import subprocess

import sys

p = subprocess.Popen(["ls","-a"], stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE)

# output one char by char

for c in iter(lambda: p.stdout.read(1), ''):

sys.stdout.write(c)

# seperate standard output and error output

stdout, stderr = p.communicate()

# output in one go

print p.stdout.read()

HTTP requests

import requests

import base64

# generate your base64 token.

usrPass = "user:password"

b64Val = base64.b64encode(usrPass)

# use postman to setup your API query and click code choose Python format

uaaurl = "https://zoneID.predix-uaa.run.asv-pr.ice.predix.io/oauth/token"

uaapayload = "grant_type=client_credentials"

uaaheaders = {

'content-type': "application/x-www-form-urlencoded",

'authorization': "Basic %s" % b64Val,

'cache-control': "no-cache",

'postman-token': "adcb4c80-f77e-f71c-f5a2-7a04ea187813"

}

uaaresponse = requests.request("POST", uaaurl, data=uaapayload, headers=uaaheaders)

print(uaaresponse.text)

Ignore exception and run next

try/except will let you catch specific exceptions and ignore to continue to run. If you need to do_thing1, do_thing2 in an order but don’t care of previous exceptions, you can have try/except for each do_thing. link

To print the exception message

try:

do something

...

except Exception,e:

print str(e)

# =====optional part below====

except (RuntimeError, TypeError, NameError):

pass

else:

raise IOError

finally:

print "This is clean-up action message."

List comprehension

row = [1,2,3,4,5,None]

# only output not None element, if must after 'for'

[x for x in row if x is not None]

# output None as xx, if else must before 'for'

[x if x is not None else '__' for x in row]

Python load data

https://s3.amazonaws.com/assets.datacamp.com/blog_assets/Cheat+Sheets/Importing_Data_Python_Cheat_Sheet.pdf

Python sort list of tuple

Sort a list based on the 2nd element of each tuple/sublist

data = [[1,2,3], [4,5,6], [7,8,9]]

data = [(1,2,3), (4,5,6), (7,8,9)]

sorted_by_second = sorted(data, key=lambda tup: tup[1])

# or

data.sort(key=lambda tup: tup[1]) # sorts in place

Sort a list based on the 2nd and 3rd element of each tuple/sublist

sorted(unsorted, key=lambda element: (element[1], element[2]))